Public side projects, a beginning

As I mentioned in my last blog entry, I will be covering my past projects and evaluating them. The only logical step is to start from the beginning, or at least close to it. This brings me back to when I was leaving college and starting my first job as a software engineer. At this time, it became clear to me that college had provided me with core foundational knowledge in computer science, but I was lacking practical application skills. To better understand the field, I decided it was time to start building some applications instead of focusing completely on algorithms and theory.

Since I had the most cliché introduction to computer science, I decided something with games would be a great start. Given this, I decided the easiest place to start would be something with text adventure games. Since I tend to lack creativity and storyline creation, I set out to create a text adventure framework so that others could create games on my system. So began one of the largest projects I have done outside of work. This was also for an audience of zero people. As far as I know, no one has ever attempted to use it.

Hello World

Energized with a fun idea, I set out to build this framework. I had decided to go in with a couple of constraints.

Built on Java

At the time, I was mostly proficient with third-generation programming languages, and the majority of code I had written was in Java and C#. At the time, I was working heavily in C#. I had justified this choice in a few different ways. First, I wanted it to be cross-platform, and I knew that Java was built to be cross-platform. This focus on cross-platform was one of the major reasons I didn't do the project in C#. Also, I knew that the all too popular up-and-coming game Minecraft was written in Java. I figured if a 3D-rendered game could run in Java, so could a text adventure engine.

Only standard Library

I had decided that if I wanted to learn something deeply, I should only use the standard library and import nothing else. In the end, I fell short of this one. While I intend to cover this more later, the notable exceptions are Java Spring, JavaFx, and IzPack.

Evolution of the project

Before we consider the end state, it seems fitting to discuss how this project evolved over time.

Early days

One of the first decisions I made was to use Maven for this project. In the earliest versions of this, I had a single project that I was working on in Eclipse and building with Maven. This started as something that I kept on my local computer and backed up on an external hard drive and flash drive for a few years. Over time, the project grew, and before I knew it, a monorepo with around nine different libraries was created.

Growing up

At some point, I had lost my flash drive. This made me realize that I could lose the project completely. After this little scare, I decided it was time to start backing up my project online. For some reason, I was worried about sharing my code publicly. So, I decided to create a Bitbucket account to back the project up in a private repository.

During this time, the industry had decided it was no longer cool to store all code in a single repository. Instead, a ton of small repositories should be managed and versioned independently. As a good engineer, obviously, I had to follow the rest of the industry. I spent a notable amount of time creating separate projects for each of my libraries. This involved breaking the library out of the monorepo, creating a new Bitbucket repository, publishing an artifact to an S3 bucket on my AWS account, just so I could download it again via Maven for the projects that depended on that code.

Getting ready for "Release"

At some point, I had decided enough is enough! “I am going to put this code on GitHub as a public repository”, and that will be my released version. I was worried that once it was out there, people would see what I was working on, so I decided to work feverishly on the project to make it "release-ready". What I defined as release-ready was the following.

First, the project needed very high test coverage. If there was a class it needed to be unit tested. It did not matter how small or pointless. To put this into context, even the about dialog in the main application had unit tests.

The next major requirement I had decided on being a "blocker" was that every public library needed to have every single method documented with Javadoc. and that all projects needed to have generated documents. This began with spending more time than I care to admit writing questionable Javadoc for absolutely everything. Then I had to fight with Maven to make sure the docs would actually generate correctly.

Lastly, if I were going to send this out into the world, every respectable program that runs on a user's machine needs an installer, right? This began a long journey of creating an install workflow. Which basically just dropped a batch script into Windows to start the game builder. In this effort, I found IzPack and spent a long time learning how to create an install flow.

Post Release

Soon after moving everything to GitHub and making everything public, I realized that no one was watching. If you want people to actually see what you are building, you need to be able to market your work, and that was not something I was good at or wanted to get good at. From that point on, I felt free to just work on the things that I had found interesting or wanted to learn.

One of the first major changes happened when I was building my personal website. I decided I wanted that website to scrape all of my GitHub content and have pages for everything I put in the docs folder of any of my projects, along with any associated Java documentation. During that time, I moved a lot of documentation. Mostly, this involved converting HTML documents that detailed how to use the application to markdown files on GitHub.

Not long after I created my website, I decided to create GitHub workflows for all my projects. During that time, all of these repositories got their own set of actions to build and test the repository on every PR. In doing this, I realized that how I was integrating with Maven and S3 was not going to work in GitHub actions. Due to this, I switched over to having my projects published to GitHub's Java repository.

At some point along the way, Java updated to Jigsaw, and I decided it would be nice to make some of my "internals" actually internal, so I updated to Java 9. I wrote about this in the following blog.

While I never really completed it, the last thing I decided to focus on was creating end-to-end tests for the main application. For this, I was playing around with test-fx. Ultimately, this never got completed because I was having a hard time getting the tests to pass on the GitHub runners. The tests had worked just fine on my local, but, for some reason I never really cared to debug, I couldn't get them to pass in the runner.

Current state of the project

Once the dust had settled, I had been working on and off on the project for close to a decade. To my knowledge, it remains used and unheard of.

Project setup

The final makeup of the project was the following repositories. While I do not think lines of code is a great metric, I do think in a pre-AI world, it highlights the amount of time spent on the project more so than anything.

| Name | Language | Purpose | Lines of code |

|---|---|---|---|

| java-core | Java | Library containing anything I deemed a core utility | 3562 |

| logrunner | Java | Abstraction to log output to csv or tsv file | 293 |

| java-persistencelib | Java | Library to save xml files to disk | 1586 |

| persist-lib | Javascript | Javascript reimplementation of java-persistencelib | 270 |

| playerlib | Java | Library for entity models and abstractions | 4100 |

| player-lib | Javascript | Javascript reimplementation of playerlib | 956 |

| playerlib-example | Java | Example application using playerlib | 1459 |

| gsmlib | Java | Library for game state models and abstractions | 935 |

| gamestate-manager | Javascript | javascript reimplemenation of gsmlib | 306 |

| iroshell | Java | Multipurpose JavaFx application shell abstraction | 10940 |

| iroshell-examples | Java | Example applications build on iroshell | 1444 |

| textadventurelib | Java | Core library required to play the text adventure games | 25045 |

| text-adventure-lib | Javascript | Javascript reimplemenation of textadventurelib | 7437 |

| textadventurecreator | Java | The main application that created text adventure games | 55066 |

In total, that is close to 115k lines of code split between Java and JavaScript.

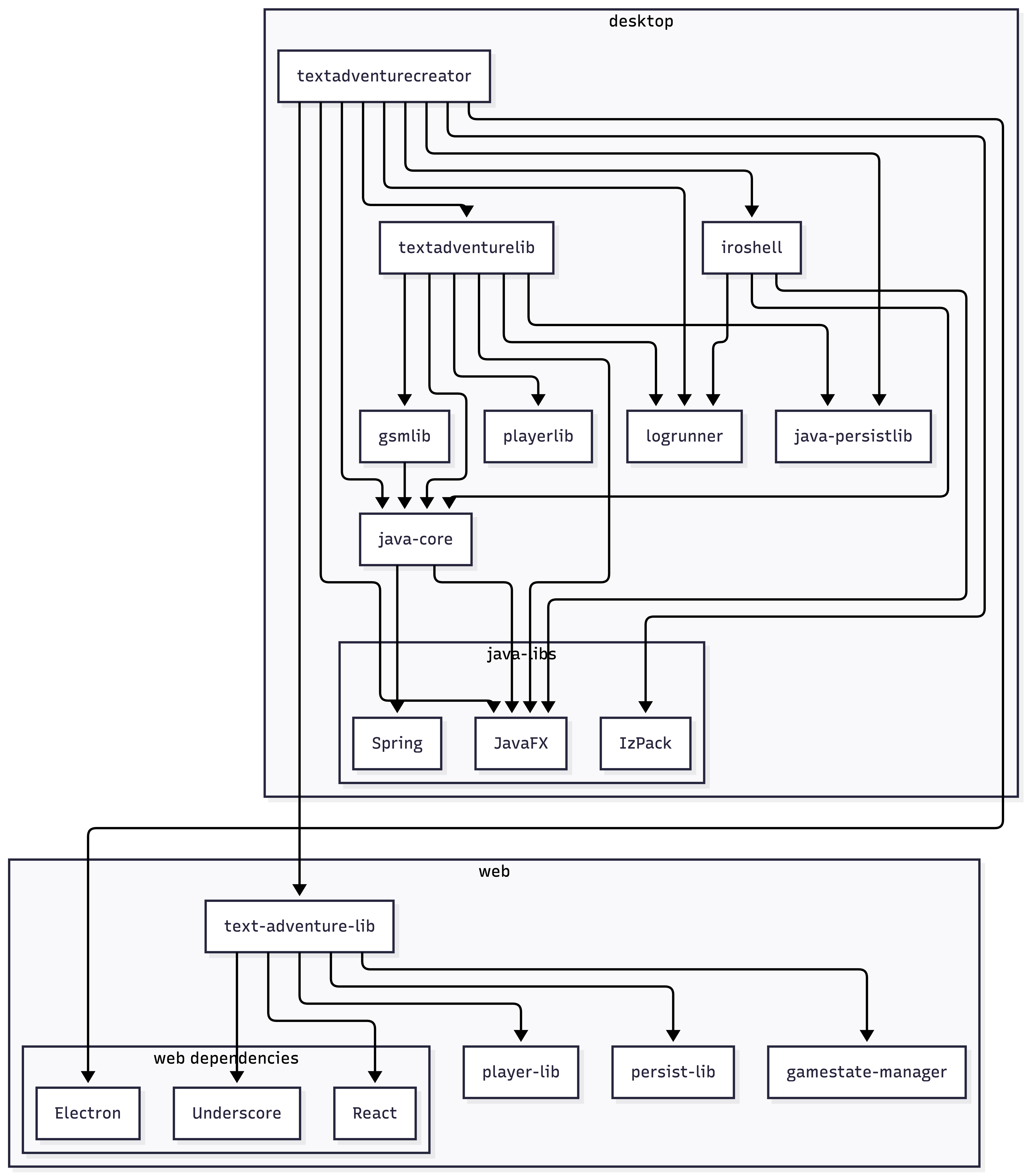

This breaks out into the following dependency graph.

Features

In the spirit of a fair analysis, I find it is useful to document all of the features wrapped up in this project. Much of this is documented on my personal site. As such, I will avoid repeating all of it. Instead, I will highlight some core features. If you are interested, the main documentation can be found here.

| Feature | Category | high level details |

|---|---|---|

| Export as App | Export | The ability to export the game as a jar |

| Export as Web | Export | The ability to export the game as an html document |

| Export as Electron | Export | The ability to export as an electron app |

| Entity creation | Core | The ability to define players and NPC's/enemies |

| Macros | Core | The ability to replace text with some player details |

| Game State creation | Core | The ability to define all actions and triggers in a game state |

| Text Trigger | Core-Triggers | The ability to trigger some action on user text |

| Timed Trigger | Core-Triggers | The ability to trigger some action on a timer |

| Player Triger | Core-Triggers | The ability to trigger some action based on player state |

| Scripted Trigger | Core-Triggers | The ability to trigger based on some executed javascript |

| Multi-part trigger | Core-Triggers | The ability to union multiple triggers together |

| Append Action | Core-Actions | Ability to add text to the game output |

| Complete Action | Core-Actions | The ability to complete a game state |

| Execute Action | Core-Actions | The ability to trigger a process on the users machine |

| Modify Player Action | Core-Actions | The ability to change player state |

| Save action | Core-Actions | The ability to save the game |

| Script action | Core-Actions | Any action that could be expressed in javascript |

| Finish action | Core-Actions | The action that completed the game |

| Text and Input View | Layout | The base look and feel |

| Text and Button View | Layout | A look and feel that replaces a text input with buttons |

| Content Only | Layout | A display only view for things like transition images or videos |

| Custom layout | Layout | A customizable grid layout of whatever controls you want for the game state, including custom styling |

| Libraries | Libraries | User defined exportable collections of players/actions/triggers or layouts |

| Debugger | DevTools | A crude debugger to see how playing the game changes the state in the IDE |

| Language Packs | Localization | The ability for users to define their own localization to be used in the IDE |

| Mods | DevTools | The ability for a developer to add a runtime loaded mod into the IDE |

Lessons learned at the project level

A warning to the reader. Many of these lessons are based on the constraints and end state of this project. If this project had been worked on by a team of engineers, my perspectives would have been different. Remember that the end state of this project is that a solo developer built something that was unused but is now in the public domain.

Just because it's on GitHub doesn't mean anyone will notice

I think this is one lesson that I wish I had learned early on. There was a fair amount of time I spent scrambling to get the code "ready for the public to view". I was concerned that once you put something on GitHub, everyone would see it. In reality, I think a handful of people have glanced at the landing page, then saw a sparse readme and moved on. The largest reader of my code may be some AI model trained on all public GitHub data.

The most important lesson for me around this is that you can waste an immense amount of time expanding code coverage and documentation on a project. If you are not working on a team and do not plan to market your work, the returns for high test coverage and documentation are questionable. The few exceptions to this would be critical or regression-prone code paths. Now, in modern times, this may be less of an investment because you could offload most of this work to an AI agent or otherwise. However, if you are going to do that, you should really scrutinize the output because it might not be documenting things correctly or testing things effectively. It is unclear to me if it is even worth the tokens or time to review to autogenerate these sorts of things for solo side projects. What is clear to me is that incorrect documentation or tests are worse than having no documentation or tests.

As far as visibility goes, what I have come to assume is that if people are going to look at your project, they will have to be led to it via some sort of marketing on social media. If you want to capture your audience, you will want a strong README with flashy images to draw their attention. I have never taken the effort to market my work, so these assumptions may be incorrect.

Industry standards are highly contextual

In this case, I made a classic junior to mid-level engineering mistake. That is adopting the mindset that the industry standard is the best practice for all use cases. Since then, I have learned that industry standards are guidelines contextualized for engineering with many active engineers working on the same project, or for domain-specific reasons.

Take, for instance, this project. I intentionally broke apart a monorepo into a series of small, targeted repositories without considering the tradeoff. In this case, I lost valuable time breaking apart a monorepo and incurred the cost of managing dependencies without getting observable benefits. Here are some cases that could have made the investment valuable, and why it remains a sunken cost.

Community involvement

I could have built a community around something like iroshell. This would have the benefit of many engineers helping me with my framework. This did not happen because I did not take an active effort to build a community. In a single instance, a developer reached out with an interest in a single part of the framework, and I chose not to engage with that engineer. If I had been truly interested in a community, I would have missed a real opportunity there.

Code Reuse

Another possible benefit I could have gotten was reuse. However, this reuse benefit would have depended on doing more Java projects that are built on iroshell, java-core, or logrunner. Instead, I have not started another Java project since this project's completion. This means I missed out on all of the hard work I put into making iroshell reusable for other possible applications.

Observing the problem space has its benefits

At no point during this work did I ever stop to look around at what other people had been doing. Had I done so, I would have found that there was already a pretty big community around tools very similar to the one I created. For instance, Twine is a rather powerful tool that can do something very similar to what I created. I do not know that this would have deterred me from taking on this project. However, taking the time to read about the project could have given me a chance to see what features others like and some of the pain points. If I wanted to create a product that got traction, that was a missed opportunity to build for the community.

Not all features are worth the investment

There are a handful of features that were either premature or questionable. In particular, the “execute action” in the game engine itself is a feature that didn’t need to be made. I am still not sure what I thought the benefit would be. As it stands, its biggest purpose is a security risk. On the premature side, features like modding and libraries had been way too early. Without a community using the tool, there was no reason to create community tools like modding.

The highlights

So far, I have been very critical of all the work I have done. However, I would be remiss if I didn't point out the benefits. On the off chance a junior to mid-level developer finds the blog and reads it, I wouldn't want to give the impression that this was a completely wasted effort. While I may have some regrets about the features I chose to work on or the way I assumed the project would be received, it was a very valuable learning lesson, even from a techinical level.

Learning JavaFX

At the start of this project, my experience with Java UIs was small college projects using Swing. At work, I was learning about C# and WPF, but those lessons had not been fully transferable. In this case, I learned how to build a framework, a UI, and auto-generated games all on top of JavaFX. I really enjoyed learning about JavaFX's use of CSS and using tools like ScenicView. While I have yet to use this knowledge in a professional setting, it was great fun to learn.

Installers

While I do not think I nailed the implementation, I did get to learn the basics of installers and the pain points of creating one. Up until this point, the software I wrote either had a team working on an installer or was just a jar/exe that someone else had to figure out how to run for themselves. In the modern era, with web-first and electron apps, this may be an irrelevant skill, but it helped remind me that different users have different machines, which may or may not have some of your prerequisites for your software to run.

It still works

With fairly minimal effort, I was able to come back to this years later and get the thing running again. The biggest pain points I had were the kinds that I expected. Mostly setting up my machine to build Java again by installing OpenJDK and Maven, as well as configuring Maven to install from GitHub.

Project completion

This was the first project I really got to play every possible role. I had the idea, oversaw all the technical decisions, implemented the entire project, designed the UX, and even did some terrible icon artwork to top it all off. I got to see this thing from a silly drawing in a notebook to a completed project that can still be used today.

In this, I learned how to stick with something even when it gets hard or boring. There were days when I would get stuck on a technical issue that I couldn't find any great documentation online. On other days, I mind-numbingly drudged through just one more Javadoc comment.

I cannot overstate how valuable that was to me. I find that when working at a company with a clear goal in mind, there are trade-offs that must be made. As an engineer, those are not always to the benefit of your technical growth. You may want to spend time optimizing a routine or playing around with a new technology/framework/language. In many cases, doing this on the job is borderline negligent and not in the interest of the company you are working for. However, when you are working on a project that is yours without direct financial incentives, you are free to make whatever choices you want. The cost incurred, in money or in time, is on you, and you do not have to consider the cost to some company.

In the modern era of AI, I am not sure if you could recreate this experience. For example, a new developer who needed an icon in a specific way might not try to draw it themselves. Instead, they might just ask an AI to generate it for them. AI can provide some excellent rubber ducking, which was just not possible when I attempted this project.

Digging deeper

By now, I have covered an exhaustive history of this application, with topics across the board. Now I want to dive deeper into the technical design choices. I will have some follow-up blogs about specific libraries and some of the technical design choices I made. This will focus on how I see those decisions now.