In my last blog entry, I detailed how I came to build a text adventure creator application. Much of that focused on high-level learning. These learnings were more focused on project structure and reception of the work. However, to do a retrospective, I wanted to focus more on the specific code choices to see what I think of them years later.

With the complicated web of dependencies created, breaking this analysis across core libraries and the application seemed appropriate. In this case, core libraries are anything other than iroshell, textadventurelib, and textadventurecreator.

Who needs telemetry anyway?

Logrunner is very small and serves a simple purpose: write log entries to a series of TSV files as well as stdout.

Now, you might think TSV is a funny format, and I will give you credit for that. However, at the time, I was using a log analysis tool that enabled querying TSV files in a SQL-like syntax, and I found that very beneficial.

In most cases, others would reach for log4j, but I didn't need those features for my purposes.

Looking back, I don't have many complaints about this library. A more advanced collection of data is required for some projects. In my case, I didn't need this kind of telemetry. If someone wanted help, they could just send me their log files.

Bad to the core

When I look back on java-core I see some obvious mistakes. If I were to start this project over, this would be a very different library. Since I made plenty of mistakes here, I will choose them carefully.

Failed wrapper abstractions

A common pattern I noticed, especially around the XML logic, is a failure to create a meaningful abstraction. In many cases, I took an existing standard library and wrapped it in a method that did the same thing. This can be a powerful abstraction if you want to switch out libraries, but in my case, I got this completely wrong. Firstly, one stated goal of this project was to use only the standard library. Wrapping the standard library with a limited feature added no value, as I was never going to use a different third party in the future. Secondly, I would wrap the standard library but return the standard library classes to the consumer. This created a leaky abstraction and did not effectively abstract out the standard library.

Failure to learn the ecosystem

If you are going to work in an ecosystem, you should use the tools from that ecosystem in the intended way. Instead, I decided to create my own pattern. Reevaluating at this library, I can elaborate on two examples where a little more time spent researching would have created less friction.

Swing is not WPF

None of this code is public, but at one point, I had a Swing-based application in the mix. This application loaded the created games and ran them. This was completely written in Swing and was created before I found JavaFX. I was influenced by WPF at the time. I was all in on MVVM (model-view-viewmodel), MVP (model-view-presenter), pick your acronym poison of choice. Of course, Swing didn't easily fit into that pattern. I could have just stuck with a single view class, as was common with Swing. However, I found it more fitting to create a monster.

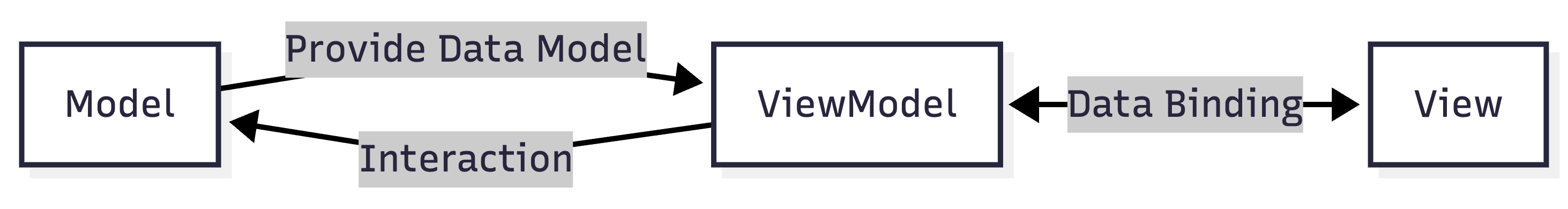

If you don't know this pattern, this analysis is most likely foreign to you. However, if you want to know or want a refresher, this is a way to separate your view and interaction/data model logic. The often stated goal is that it is easier to have "just UI" and "just behavior" changes. The flow between components is relevant, so here is a visual aid.

To create a similar effect, I decided on using: a model with no view logic, a view that was the Swing control, and a presenter. The implementation was an absolute mess. I ended up having all views and models extend from some base classes. These base classes would then allow you to raise a change event. This event would then be picked up by the presenter, and the presenter would use reflection to invoke the appropriate method on the linked view or model. This produced completely absurd code and failed to meet the desired abstraction.

Not only did this build MVP incorrectly, but it forced you to pay the reflection tax. If I had scaled up this pattern, the application would have run much slower, as none of the UI interactions would have been able to be effectively JITted.

Localization is solved in the standard library

Another mistake I made in the implementation was creating my own language file format for localization. If I had done a little research, I would have found that Java has a robust solution for localization. Instead, I created an abstraction that was very similar to standard properties files but used the delimiter ;=; instead of =.

Pulling in Spring

I have no issue with Spring, but one of my stated goals was to only use the standard library. Instead, I pulled in one of the biggest common libraries for a very small purpose. I wanted to be able to do IoC, and Spring had it. In doing so, I saved myself a headache by not trying to implement IoC myself, but I missed out on some of the learning I wanted to achieve.

Data formats are tricky

Much of what I built takes in an abstract state, serializes it to XML, then reads it back into classes. When I created this abstraction, I assumed I would eventually use other formats. The problem is, I made a very classic mistake. I built an abstraction before I had multiple use cases. This ended in a poor abstraction that was the Java XML library with a few opinions. At one point, I had considered adding JSON support, but the abstraction I had built didn't make sense for any other data format. What the heck does it even mean to add an attribute to a JSON property?

Building an entity model

The core of playerlib is the ability to create an entity that describes how I thought a player should work. This entity had many opinions about players. Players have attributes, characteristics, inventory, and so on. This even built in some features, such as listening for changes to the player entity.

I didn't have too much of a problem with this, but then I remembered something. There was one thing that this abstraction did, which caused me much grief. The value type was not known at compile time. Let's take a simple example: a player can have attributes. In these attributes, there can be different value types. For example, you might have an attribute age that is an int and another attribute surname that is a string. The original implementation stored the value as an Object. The caller of the code had to figure out how to unwrap the value. Later on, I remembered that Java had generics; certainly, those would fix my problem! Of course, that wasn't quite right in my implementation. What I effectively did was take a method like this

Object getValue();and turn it into this mess.

<T> T getValue();Now, in hindsight, there are probably a couple of ways I could have made this easier to reason about. One option would have been to create a pseudo-type union.

enum ValueType {

String,

Integer,

Double,

Boolean

}

abstract class BaseValue {

private ValueType valueType;

public BaseValue(ValueType valueType) {

this.valueType = valueType;

}

}

class StringValue extends BaseValue {

private String value;

public StringValue(String value) {

super(ValueType.String);

this.value = value;

}

public String value() {

return this.value;

}

}

class IntValue extends BaseValue {

private int value;

public StringValue(int value) {

super(ValueType.Integer);

this.value = value;

}

public int value() {

return this.value;

}

}

// etcThis would have removed many type checks that had not been applied consistently. In addition, it would have allowed for unboxing primitive value types.

Building a state machine

In gsmlib, I assumed that I could represent any possible game with the abstraction created. This mental model being all games are a series of game states, and there is data that moves between states. Also, all games would have a finished state. This state would tell you the game is over. In addition, there was a concept of game state buffering. For buffering, you would be able to load a couple of game states into memory. Then, as the game states proceed, the current game state would be evaluated to load the next game states needed.

I don't have much to complain about with this abstraction. However, to be fair in this analysis, I must admit that this had the same shortcoming as playerlib. The game state data that was passed around from game state to game state was Object and did cause some issues. This also made an overgeneralization; this clearly would not apply to all possible games. In essence, I just created another state machine.

So what did I learn?

If I had to distill this long analysis down into key lessons learned, this would be the TL;DR.

Take some time to read about the ecosystem. Reinventing patterns in an ecosystem is rarely to your benefit. This is doubly true if you are a junior. You can learn a lot doing this, but more often than not, you are just creating a mess.

Have more than one implementation before creating an abstraction. Failure to do otherwise will create a premature abstraction that is almost certainly insufficient.

If your abstraction is clever, it's probably wrong. Just because you can do something and get it working doesn't mean it was a good idea. Consider your trade-offs and understand the cost you are paying.

Strong types are preferred. If you are just passing Object around or accepting a generic whose type hint cannot be statically inferred, you are going to end up paying for it in the future. The runtime cost to find the underlying type is not free, and the developer time wasted writing and maintaining that code will be staggering.